april 2014

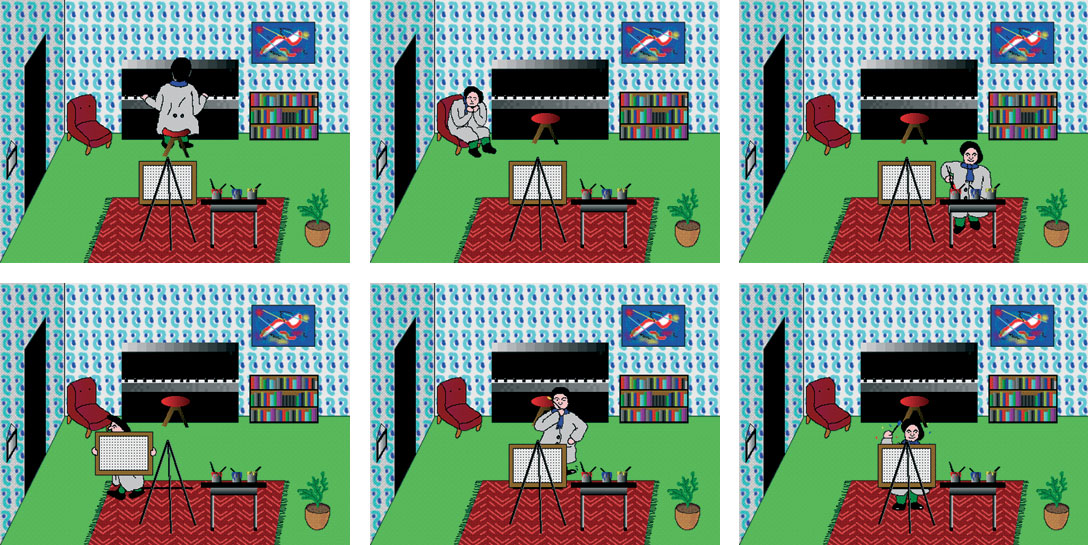

Réveillé par l’activation d’une horloge interne, Raoul n’a nul besoin de se lever, il apparaît morceau après morceau, tel un fantôme, dans la pièce qui lui sert d’atelier. Pendant quelques courts instants, insuffisamment assuré de son identité personnelle, il s’oublie dans les choses, se trouve emmêlé dans le trapèze au vert éclatant de la moquette ou happé, en partie, par le dessin aux barres de couleur verticales qui schématise une bibliothèque.

Dès qu’il se sent un peu mieux lui-même, Raoul commence à s’adonner avec ferveur à sa principale activité: marcher. Cet exercice ne constitue pas un but en soi, il signale la perplexité de l’artiste. Béret vissé sur le crâne, affublé d’une blouse grise dans le dos de laquelle il a pour habitude de croiser ses mains, Raoul expérimente l’espace de l’atelier avec une touchante maladresse. C’est au moment de changer de direction qu’il semble éprouver le plus de difficultés… n’est-ce pas qu’il s’affronte alors à une aporie spatiale: comment s’orienter dans la profondeur illusoire d’un plan? Métaphore du problème auquel s’est toujours confrontée la peinture, la déambulation de Raoul n’a plus pour vertu de prouver le mouvement par l’exercice mais bien d’affirmer la possibilité de la représentation. Peintre, – Pictor – Raoul l’est tout d’abord par sa démarche, préambule obligé de son art.

Pour se reposer de ses graves préoccupations, le peintre a l’habitude de jouer du piano. Il prend aussi des pauses en s’abandonnant au confort un peu fruste d’un fauteuil niché dans un angle de la pièce, situation privilégiée pour qui prétend scruter l’orthogonalité du monde phénoménal. Ensuite, Raoul peint vite, avec une ferveur inquiète, dans l’urgence de fixer, avant qu’il ne lui échappe, le résultat de méditations longuement ruminées durant ses va-et-vient. Artiste d’atelier, son modèle est mental. Nulle image, vignette pittoresque ou vision sublime, ne vient troubler sa claire conscience des rapports. La toile achevée à grands coups de brosse, après force gesticulations, l’artiste la prend à bras-le-corps et quitte avec elle la pièce par une étroite fente noire; laquelle fente, si l’on accorde quelque crédit au code perspectif que nous a légué la Renaissance, symbolise une ouverture rectangulaire au format d’une porte.

A noter: nous ne savons rien de l’œuvre qui vient d’être achevée puisqu’elle était posée de dos sur le chevalet qui occupe le centre de l’atelier et que l’artiste s’en est saisi, une fois terminée, sans la retourner. Pour l’heure, Raoul, revenu à son état électrique primordial, lié à sa création si intimement que plus rien ne les distingue l’un de l’autre, Raoul privé de surface, Raoul l’algorithme circule dans le réseau des câbles, à cheval sur l’interface qui relie imprimante et ordinateur. De son activité sans représentation naît une image: jeu d’encres colorées obtenu par la réunion dans un format paysage d’une sélection aléatoire d’éléments emmagasinés dans la mémoire d’un programme. Signée, datée et numérotée, l’œuvre actualise un des termes de l’ensemble des probabilités à quoi se résume, pour finir, l’élan créateur de Raoul. Dès lors quelques questions se font pressantes:

L’expression “Raoul Pictor cherche son style…” signifie-t-elle qu’il l’aura trouvé lorsque, la musique du hasard s’étant tue, il aura épuisé toutes les combinaisons possibles – à savoir, plusieurs milliards, sans doute – à partir des données limitées de sa mémoire? Dans cette hypothèse, si Raoul continue à produire, il ne pourra plus que se plagier lui-même. Faut-il voir là une forme de radotage ou bien considérer plutôt qu’il nous donne une magnifique leçon sur les mécanismes mystérieux qui font agir les artistes? œuvre d’art, quelle que soit sa forme, quelque matériau qu’elle emprunte pour incarner cette forme, n’est-elle pas fondamentalement dépourvue d’originalité? Au public enthousiaste qui applaudit la nouveauté radicale faute de reconnaître, sous l’éclat trompeur de son actualité, une réorganisation habile ou inspirée du même, Raoul oppose une conception moins idéaliste de la création. Qu’après x années de son inlassable labeur, il commence à peindre des toiles déjà une fois sorties de son atelier, on ne peut raisonnablement le lui reprocher puisqu’au regard de sa mémoire achevée, son œuvre complet existe, au moins potentiellement, avant même qu’il ait préparé sa palette. Une peinture qui sort de l’imprimante est donc, de fait, toujours une copie. En quoi le fait d’être la première constituerait-il un statut privilégié? Quelle légitimité ontologique particulière pourrait-on lui accorder qui interdise qu’une seconde puis une troisième copie, et ainsi de suite, soient à leur tour produites? A la question qui inaugurait ce chapitre d’interrogations, on fera écho par celle-ci, qui ne prétend pas le clore: Est-ce donc qu’à la différence de beaucoup, qui un jour ont cru trouver, Raoul, scrutant le corpus immense mais fini de ce qu’il a à exprimer, cherche encore?

F. Y. MORIN

Awakened by the activation of an internal clock, Raoul appears to us piece by piece, like a ghost, in the room which he uses as his studio. For a few moments, not yet sure of his personal identity, he loses himself in his surroundings, becomes entangled in the bright green trapezium of the fitted carpet or partly snatched up in the drawing of a bookcase, simplified by vertical bars of colour.

As soon as he finds himself, Raoul fervently undertakes his main activity: walking. This exercise is not a goal in itself, it indicates the perplexity of the artist. Decked out in a grey smock, beret fixed onto his head, his hands linked behind his back, Raoul tries out the space in his studio with a touching clumsiness. But when he changes direction he seems to face certain difficulties… is he not confronted with a spatial aporia: how to adjust himself to the illusionary depth of a plane? Raoul’s pacing, a metaphor for the problem of depth, that forever confronts painting, no longer has the virtue of proving motion by doing it, but asserts the possibility of representation. Raoul is a painter – Pictor – primarily by his pacing, obligatory preamble to his art.

To put aside his solemn absorptions the painter is accustomed to playing the piano. During his breaks he also abandons himself in a crudely comfortable armchair nestled into a corner of the room, privileged position for whoever pretends to scrutinize the orthogonality of the phenomenal world. After which, Raoul paints quickly, with an uneasy fervour, in his urgency to fix the outcome of his meditations, longly chewed over during all his comings and goings, before it escapes him. Being a studio-artist his model is mental. No image, picturesque vignette or sublime vision, comes to trouble his clear awareness of relationships. The canvas is finished with large brush-strokes and many gestures, whereupon the artist takes it under his arm and leaves the room by a narrow dark opening; this opening, if we are to grant credit to the Renaissance codes of perspective, symbolises a rectangular opening in the shape of a door.

To note: we know nothing of the work that has just been completed as it was placed on an easel with its back to us, taking the centre position in the studio, and the artist, after having finished his work, took it away without turning it. For the moment Raoul, who has reverted to his primordial electrical state, is linked so intimately to his creation that we can no longer distinguish one from the other, Raoul deprived of a surface, Raoul the algorithm moving in the network of cables, straddling the interface that connects the printer and the computer. From his unrepresented activity, an image is born: a pattern of coloured inks obtained by combining in a landscape format a random selection of elements stored in the programme’s memory. Signed, dated and numbered the work then represents merely one of the terms of the set of probabilities to which Raoul’s creative fervour finally boils down. From here several pressing questions are to be posed:

Does the expression Raoul Pictor seeks his style signify that it will have been found once the music of chance has died, when he has exhausted all possible combinations – without doubt many billions – within the limited framework of his memory? In this hypothesis, if Raoul continues to produce, there will be nothing left for him except to plagiarise himself. Is one to see here a form of rambling or rather consider this as a wonderful lesson in the mysterious mechanics that make artists act? Is not the work of art, whatever its form, whatever materials are employed to embody the form, fundamentally lacking in originality? To the appreciation of the enthusiastic public, which applauds a radical novelty, failing to recognize, beneath the glaring deception of its topicality, a deft or inspired reorganisation of sameness, Raoul offers a less idealistic conception of creation. If after x years of hard labour, he begins to paint canvases that have already come out of his studio, can one fairly reproach him for it, knowing that within his achieved memory his completed work exists, at least potentially, even before he has prepared his palette? A painting that comes out of a printer is therefore always a copy. What privileged status then does the first copy hold? Is it possible to give an ontological legitimacy prohibiting a second or third copy, and finally to them all being reproduced? To the question that opens this passage, we echo the following one, with no pretention of closing the subject: Is it then that, unlike many, who one day believed they had found, Raoul, scrutinizing the boundless but finite corpus of what he has to express, continues to seek?

F. Y. MORIN

(Trad. V. Sordat, D. White)